The Fouling While Up Three Problem

We need more late-game drama

“The smartest way to play is not the most attractive way to play.”

- Nick Wright, The Bill Simmons Podcast

The NBA is under fire. And that’s a good thing. When people complain, it’s a sign they care.

My last post explored how offensive player movement has been manipulated to draw fouls, partly due to the growing influence of analytics. There has been a healthy debate as to whether analytics makes the sports viewing experience better or worse. Depending on who you ask, you will get different answers.

Either way, I think most fans can agree that we watch sports to be entertained. We watch to feel something. We want to live out our past glory days. Remember the game-winner we hit in our driveway, or if we’re lucky, our high school gymnasium.

Pause for a second and think about your favorite NBA games. It may be a player’s performance over the course of 48 minutes, or it may be some outstanding athletic feat. Most likely, it’s a memory as the time is running down.

We feel something when the games are tense, there is drama to be viewed, and the clock is about to hit zero. Everyone loves a last-second buzzer-beater. It’s what gets the fans jumping up and down wildly at the bar, in a living room, or in the arena.

One analytics movement has started to slowly remove buzzer beaters from the game—fouling while up three. It feels like more and more games are now ending at the free-throw line instead of with a well-executed and defended ATO. Those nail-bitters are now turning into snoozers, and it’s bad for the NBA product.

There have been several studies on the effectiveness of fouling while up three, a few of which I will review. The results of the studies haven’t always been the same, but I’ll explain why as we go along.

Math & Probabilities

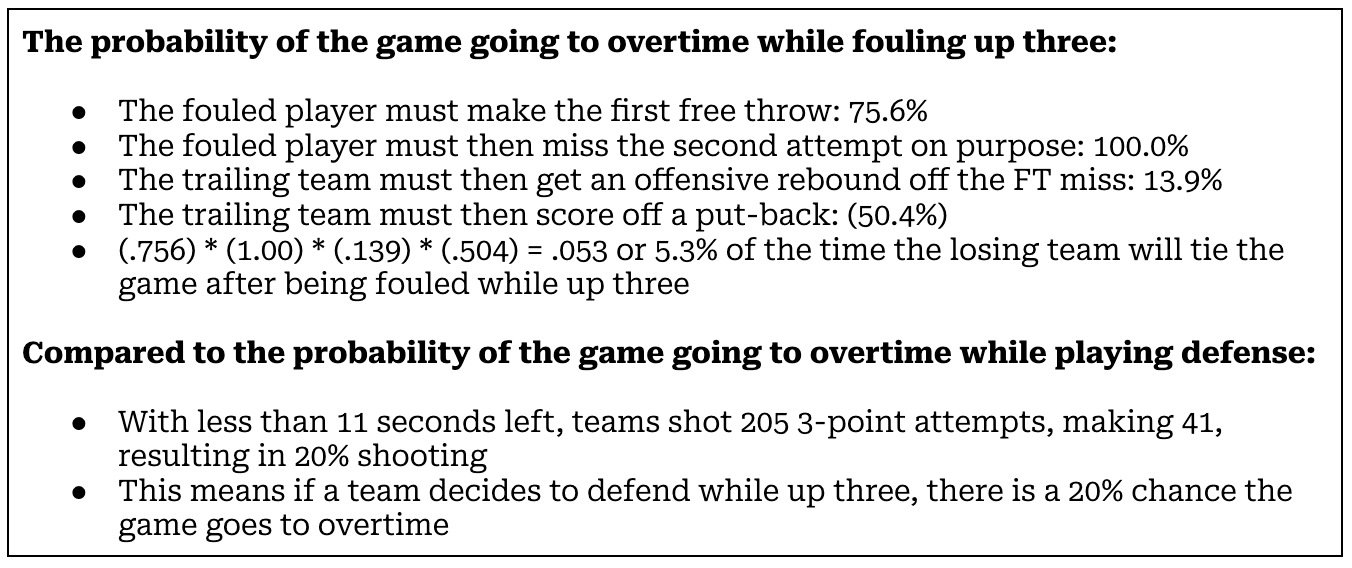

An analysis was conducted 20 years ago by a math professor named Adrian Lawhorn. He used math and probability based on NBA shooting and offensive rebounding percentages.

Lawhorn played out the two scenarios of fouling while up three or defending straight up. He concluded that fouling while up three would result in teams being 4x more likely to win vs having the game go to overtime.

Still, for 20 years, most coaches didn’t view fouling while up three as a viable option. Data wasn’t as accessible and it wasn’t something teams seriously considered.

Not Segmenting the Data by Time Remaining

There is another group of studies that analyzed fouling while up three vs defending straight up based on historical winning percentage data for each scenario.

In 2008, another professor named Wayne Winston shared that one of his students observed the data of all NBA games between 2005 and 2008 in which a team was down three with under 10 seconds left.

The leading team played defense 260 times and won 91.9% of the games. Of the 27 times the leading team fouled, they won 88.9% of the games. The analysis concluded that no definitive strategy was better or worse than the other, a drastically different outcome than the study two years prior.

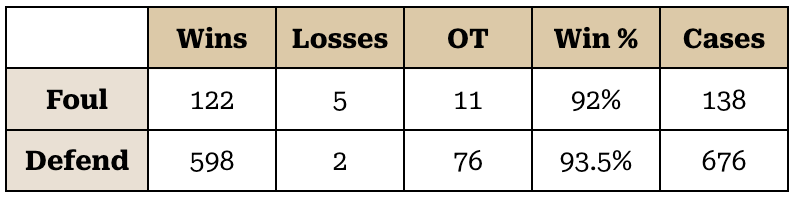

Then, in 2013, Ken Pomeroy, a college basketball analytics guru, conducted his own study at the college level. He looked at all possessions when the team trailing by three had the ball with between five and 12 seconds left at the end of the second half or overtime.

The 676 teams that decided to defend won 93.5% of the time compared to 92.5% of the 138 teams that decided to foul. Again, a similar result to the 2008 study, with playing defense appearing like the slightly better strategy.

In 2020, Pomeroy wrote another article on the subject of fouling up three, but instead of looking at the data, he identified a loophole in the rule:

“One creative solution to the end-game conundrum is to foul up three and commit lane violations on the last free throw until the shooting team makes it. If you’re a rules wonk, you know that if the defense violates the lane, it’s only penalized if the shooting team misses. This is a feature and not a bug: The shooting team gets the result that benefits it — either a point or a do-over. But in the foul-up-three situation, it is a bug. The fouled team wants to miss, but it isn’t allowed to do so as long as there are violations.”

Intentionally committing lane violations hasn’t ever been a strategy I’ve seen used. However, if it does become a problem, changing the rule to call a technical foul for intentionally gaming the rules would quickly fix the loophole.

Lastly, additional analysis was conducted on NBA data in 2024. Researchers looked at games when a team was leading by three with 24 or fewer seconds remaining. Teams that elected to play defense won the game 93% of the time. Teams that fouled won 92% of the time.

It is clear that there isn’t much difference between fouling and playing defense when the data isn’t segmented by time remaining. Still, all three studies suggest playing defense might have a better winning percentage.

As you will see, though, analyzing the data using a different methodology yields a different result.

Evaluating Probabilities Based on Remaining Time

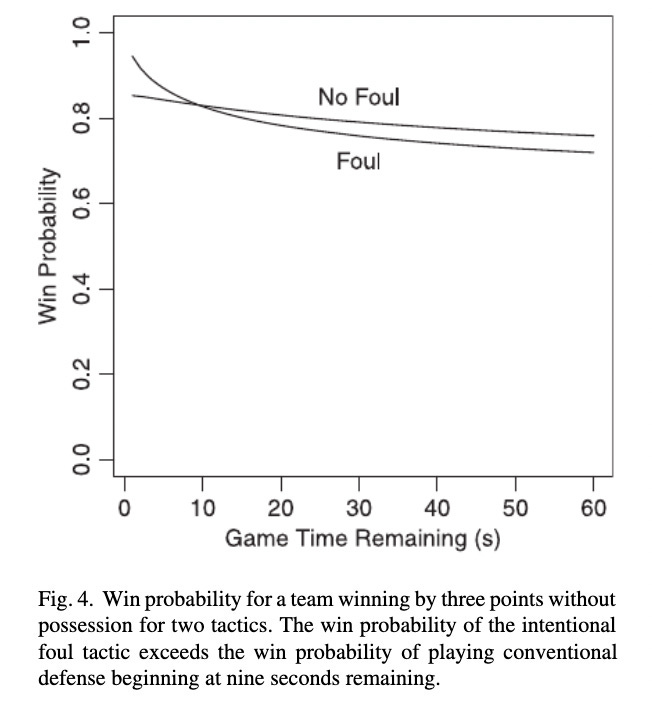

Another group of studies considers the exact time remaining in the game when deciding whether fouling or defending is the better strategy.

In 2018, Patrick McFarlane, an analyst of the Philadelphia Phillies, looked at NBA games and found that with about 36 seconds remaining, playing defense gives the team up three a 3.5% better chance of winning than fouling would.

However, at around nine seconds, intentionally fouling becomes the optimal strategy. With one second remaining, fouling gives the team up three a 9.2% better chance compared to defending regularly.

Obviously, fouling with only one second remaining can be trickier said than done because you are more likely to foul a shooter. However, the principle remains the same—stick with traditional defense until around nine seconds remain in the game.

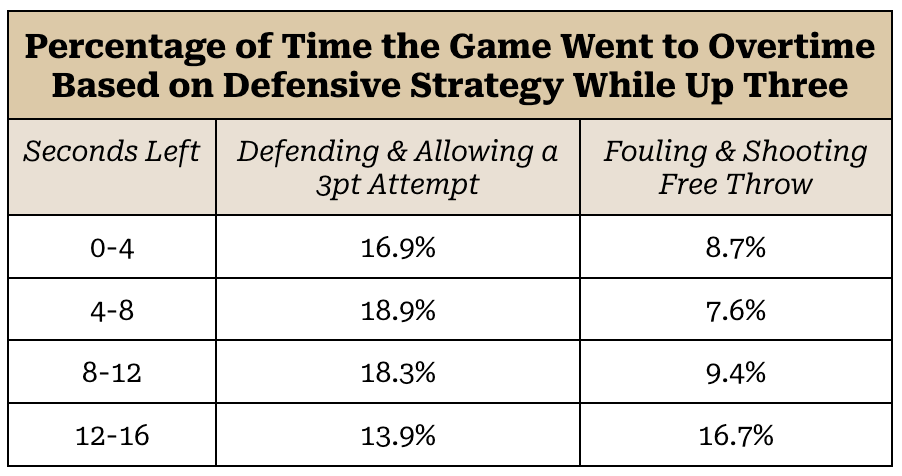

A similar analysis was conducted in 2022 with college basketball data. The study observed three-point games with 16 seconds or fewer remaining when the losing team had the ball. It sorted the data based on teams that chose to defend and allow a three-point attempt vs teams that fouled, leading to foul shots. Similar to McFarlane’s analysis, it cut the data based on the time remaining in the game.

For games between 0-12 seconds, fouling while up three doubled the chances of winning in regulation vs having the game go to overtime. Fouling between 12-16 seconds remaining actually flipped the script, with a higher percentage of games going to overtime.

The Optimal Strategy

Each of these studies has slightly different timeframes and datapoints. But as you can see, cutting the data by time remaining in the game sheds new light on the fouling while up three vs defending strategy.

It is reasonable to believe that a well-trained analytics department can analyze the data and instruct a coaching staff when to foul vs not, depending on how much time is left on the clock. Based on the mounting evidence, determining a team’s strategy based on the time remaining seems to be the correct decision.

It’s only a matter of time before we see almost every team perfect the fouling while up three strategy. With the mountains of data now available to the public and as coaches come under more scrutiny for their decisions (or lack thereof), coaches will almost always do what the probabilities suggest.

The Best Outcome for Fans

Still, as mentioned at the beginning of this post, I wondered out loud if this strategy is good for basketball. Nail-biters are turning into snoozers as the final minute of the 4th quarter is turning into 20-minute ordeals.

So, what are we to do?

The NBA changed rules after the Hack-a-Shaq trend in the early 2000s, penalizing teams for intentionally fouling a player off the ball in the final two minutes. Doing so would result in one free throw and the ball back for the offensive team.

The NBA clearly wants the game to be more entertaining. Just look at how defenses are hamstrung nowadays.

There are possible avenues to make a rule change to eliminate fouling while up three. It’s just not as straightforward as the Hack-a-Shaq rule change.

The NBA might learn a thing or two by observing FIBA, which has what they call an unsportsmanlike foul. Its rulebook states:

“An unsportsmanlike foul is a player contact which, in the judgment of a referee, is contact with an opponent and not legitimately attempting to directly play the ball within the spirit and intent of the rules.”

The NBA could implement something similar, which would result in free throw(s) and the ball. It would incentivize more aggressive defense, which I view as a positive. But should this rule be applied to both teams or just the team winning at the end of the game? Or should it be applied throughout the whole game?

The challenge is that it becomes more of a judgment call for referees. Introducing more judgment will lead to mistakes. It could also lead to more intentional fouls disguised as normal fouls.

I’m not here with all the answers. You can scour the internet and see many different suggestions—using Elam scoring in the 4th quarter, allowing offensive teams to decline free throws similar to teams declining penalties in football, etc.

All have some sort of flaw that doesn’t quite sit right with me. Surely, there are people smarter than me whom the NBA can employ to figure it out. I hope so. I’d like to get back to more exciting late-game drama.