Data on the NBA's Achilles Injury Epidemic

Hypotheses on why players are succumbing to this devastating injury

Dame Lillard was waived, and his contract was stretched. The Milwaukee Bucks would rather have $22 million of dead money on their cap for the next five seasons than have him on its roster. Brutal.

Lillard’s recent Achilles tear likely has a lot to do with this decision. If the upward trend in Achilles injuries persists, other teams may face a similar decision.

The NBA has already assembled a panel to understand the rise in Achilles injuries. Just this last season we saw eight Achilles tears. Previously, the most in one season was four. The NBA is hopeful they can find some answers. Said Adam Silver,

"I'm hopeful that by looking at more data, by looking at patterns, the ability with AI to ingest all video of every game a player's played in to see if you can detect some pattern that we didn't realize that leads to an Achilles injury. We're taking it very seriously."

I analyzed Achilles injuries since 1992 and considered factors that could have contributed to each of the Achilles ruptures.

All but one reported Achilles tear happened during non-contact plays. Most commonly, players step backward and plant their back foot as they attempt to push off and gain momentum when their Achilles gives out.

As you can see from the chart below, this often occurs when driving to the basket or going after a loose ball. Whether this movement is preventable is up for debate and one I am not qualified to answer.

Many have already formed their own opinions speculating on what is causing the uptick of the devastating injury. We've heard everything. One factor could be the increased pace of the game combined with more explosive players. Another factor could be that athletes are playing single sports year-round from a younger and younger age. Some continue to blame the 82-game schedule.

All of these likely play a role in Achilles injuries in the NBA. I turned to the available data (which isn't a lot given the small sample) to uncover possible reasons for Achilles injuries. The data doesn't prove or disprove any one culprit but helps to better explain potential theories.

Increased Load

I have previously written on load management, the act of sitting players to rest them to try to prevent future injuries. One of the main takeaways from my piece was that load management could potentially cause more injuries if not careful.

The reason for this is that as load is increased on players' muscles and joints, a player's body can break down if it isn't properly adjusted to the increased load.

Here's a practical example: If a player comes off a prior injury and has been sitting for two weeks without game action, they may be out of shape. Once they return, their body experiences an increase in physical load that it isn't accustomed to, which can cause stress.

So that's exactly where I started. As I scoured injury reports for players who ruptured their Achilles, about half of them had just come off a previous injury either related or unrelated to their Achilles. It is possible that many players who tore an Achilles just weren't in game shape and exerted too much stress on their Achilles too soon. Lillard is the perfect prototype for this theory.

Similarly, I also looked at minutes per game of players who tore their Achilles. Playing in the 30-40 minute range seems to increase the likelihood of injuries. However, there are plenty of players who have torn their Achilles and averaged in the 0-20 minute range per game.

This could also point towards introducing too much stress without being in game shape. It's no secret that NBA teams practice far fewer times throughout a season compared to the past. Perhaps a lack of practice introduces injury risk, especially for those who aren't playing big minutes.

In the same vein, more players have torn their Achilles having played less than 25 games in a season compared to those who have played more than 75. Again, maybe too much load too quickly into a season increases injury risk.

Pace

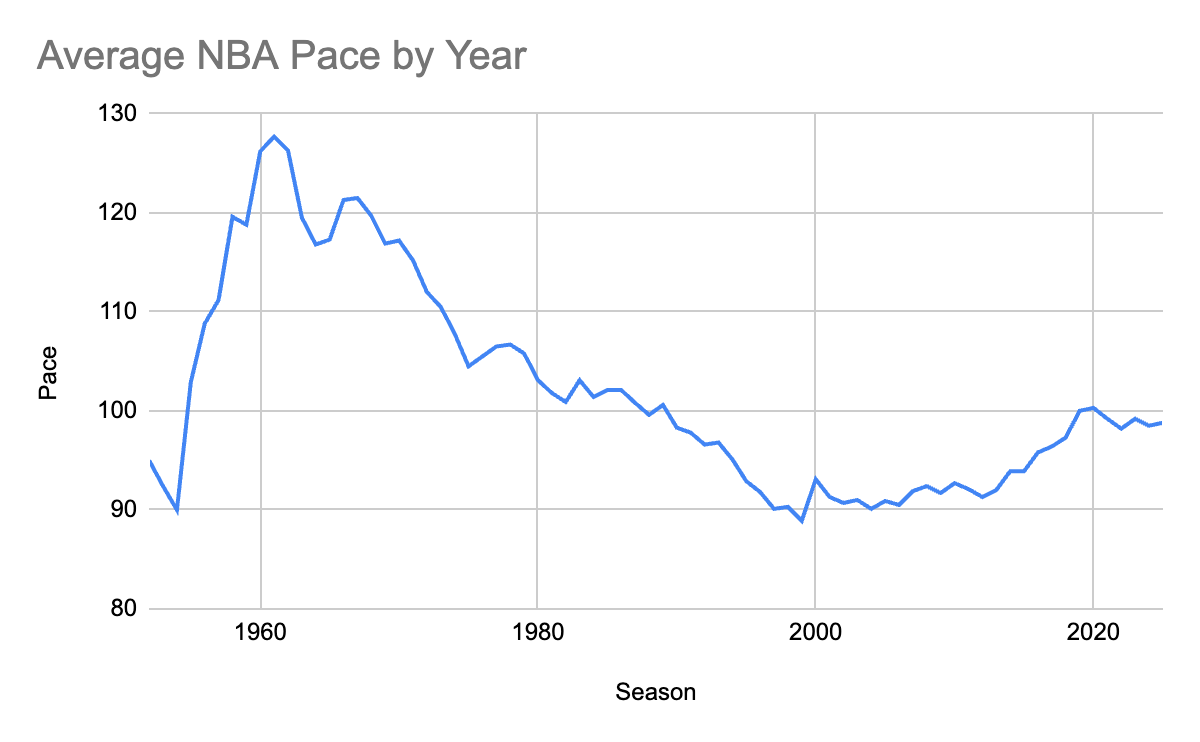

Over the last 20 seasons, we've seen the pace of NBA games increase dramatically. Teams are now averaging about 10 more possessions per game compared to the early 2000s. Due to the increase in pace, we are also seeing players cover more miles on the basketball court per 82 games since the early 2000s—about 200 more miles in fact.

At the same time, there is a correlation with an increase in Achilles injuries. It appears that as the pace of the game increases, more Achilles injuries are occurring. However, this argument breaks down once you go back further in time.

The pace in the 60s and 70s was crazy high. In fact, between 1955 and 1988, pace never dipped below 100 possessions per 48 minutes. In the early 1960s, pace peaked to over 125. Compare that to today's NBA where we thought the pace was fast (at least compared to the 2000s). Last season's average pace was only 98.8 possessions per 48 minutes.

Now, we don't have as much data on Achilles injuries back in the 60s and 70s, but all indicators point towards today's NBA producing the most Achilles injuries. If pace were the sole reason for an increase in Achilles injuries, we should have seen more back in the day.

Weight

I explored other factors that could impact Achilles injuries and weight stuck out to me as a possible culprit. Since around 1980, basketball players have continued to get heavier despite the average height of the NBA remaining flat. On the surface, an increase in weight also seems to correlate with an increase in Achilles injuries.

I created what I am calling a weight-to-height ratio. I divided the players' weight by their height (cm) to come up with a score for each player who ruptured an Achilles and compared it to the league average weight-to-height ratio.

What I found was that players from 1992-2009 who tore their Achilles had a higher weight-to-height ratio than the league average. However, since 2010, players who have ruptured their Achilles actually have a slightly lower weight-to-height ratio.

Again, we can't claim causation, but my best hypothesis for this is that when the pace was the slowest it has ever been in the NBA, more and more players bulked up, which could have caused additional wear on players' Achilles.

As the pace of the NBA has increased over the last 15 years, perhaps it has become a bigger factor in Achilles injuries as players have slimmed down and introduced higher loads on their bodies all at once.

Again, if we look back at the 60s and 70s, the pace was still much higher than it is today. However, the players' weight was much lower. The average player back then was a good 10-15 pounds lighter than today. More agility and less bulk could be beneficial in preventing injuries when the pace increases.

This argument feels logical, especially if you look at other sports that have similar side-to-side cutting movements and changes in direction. Tennis is the first sport that comes to mind and those athletes are much leaner than basketball players.

Cumulative Load

I also looked at the cumulative load throughout a career. From 1992-2009, the average age of a player who ruptured their Achilles was 29.9. Given that an Achilles tear was known as an "old man's injury," an average of nearly 30 years old seems reasonable.

However, the age of players who rupture their Achilles has decreased since 2010 to 27.5. This is the prime of someone's career, and being derailed for 12+ months with an Achilles injury definitely shouldn't be something a player and training staff should be worrying about.

Similarly, the number of seasons a player plays before accruing an Achilles injury has declined. Just look at this scatter plot below. From 2010 until today, the average number of seasons played in the NBA before an Achilles tear was 7.0. Compare that to the average number of seasons played between 1992-2009 before rupturing an Achilles and it was 8.5 seasons.

The number of players who have played fewer than five years while sustaining an Achilles injury has increased dramatically over the last 10 years.

Again, all of this could point to the increased miles and wear NBA athletes' bodies are being put through, not to mention the increased focus on playing a single sport year-round at the youth level.

Key Takeaways

As mentioned at the beginning, there likely isn't one reason we are seeing more Achilles injuries in recent years. It is probably a combination of a few factors that has created the perfect storm. Too much load among players who aren't in game shape, prior injuries, an increase in pace, weight, and cumulative load all likely impacted recent Achilles injuries.

I'm hopeful the NBA will release their data on Achilles injuries. However, if it's anything like their study on load management, they will likely keep most of their findings under wraps. Until then, we can only hope the NBA, team trainers, and individual players do what they can to prevent injuries and preserve the product on the court.

I’d be curious if you could compare MPG and GP for injured players against their previous season or previous career avg to see if the injury season was an overall higher load