FC Red Bull: More Than an Energy Drink

The blueprint to building a football empire

A little over 10 years ago, I spent a couple of months in Ghana during the summer. Outside of the hostel where I stayed lived a few teenage boys. They lived and slept on the floor of a little shed.

We became friends with them. Our most common interest was football/soccer. They invited me and a few others to one of their games, where we watched them play on a dirt field. Their dream, like thousands of other kids, was to play at the top levels. At the time, I wondered, "How do any scouts find these young players?"

Somehow, scouts do find them, on a random dirt field in the middle of Accra, Ghana. Football is the most global game in the world. Look at any roster, and you will find players from every corner of the earth. And it's made possible because of the intricate web of global scouting networks.

Clubs have extensive networks worldwide and in key geographical regions. Oftentimes, it's trusted locals, youth coaches, and former players scattered throughout cities and villages who will first notify a scout or club about a talent. When scouts get a call, they will travel on bumpy roads to see a prospect play.

Some of the top clubs have feeder academies or partner with local clubs and training centers in places such as West Africa, Brazil, and Eastern Europe. The clubs will snatch up the best players as they emerge from their local clubs. An example of this is the Right to Dream Academy in Ghana, which has direct ties to Nordsjælland in Denmark. It's a great gig for the youth players, knowing that there is a direct path to Europe if they succeed. Such was the case for Mohammed Kudus.

Scouts are often prowling the sidelines of youth tournaments. It's not unheard of for a scout to show up to a game that happens sporadically in the streets. Scouts will touch down in a country and sometimes not leave for months, jumping from game to game. More frequently, scouts are turning to cell phone video footage sent to them via WhatsApp. It is often a video that sparks a scout's initial interest.

For players, it can be a matter of being seen at the right time. Sadio Mané is a classic example, after being spotted in Senegal at the age of 15. He joined a well-known club in Dakar, the capital of Senegal. After succeeding there, he was signed to a French team, where he impressed in Ligue 2. He then joined Red Bull Salzburg in Austria before finally making his way to the Premier League.

Red Bull the Football Club

Mané's stint with Red Bull Salzburg is no coincidence. What is known as an energy drink by most is building a football empire. Many have probably seen the Red Bull logo on different football team jerseys. However, it isn't just a sponsor for a couple of random football clubs. Red Bull is a football club. Plural.

SSV Makranstädt was a fledgling club in Germany bouncing around the lower divisions. In 2009, Red Bull decided to purchase licensing rights to Makranstädt, which eventually led to it owning most of the club's voting rights through a few German footballing rules being bent.

One of those rules is that teams can't be named after their sponsors, but Red Bull decided to change the name of the team to "Rasenballsport Leipzig." Rasenballsport literally means "lawn ball sports," which seems rather embarrassing for a professional sports team. However, Red Bull didn't care because the team name could then be abbreviated to RB Leipzig. The new abbreviated name, coupled with a big Red Bull logo on the front of the jersey, meant everyone now associated Red Bull with the team.

Meanwhile, Leipzig started winning. Within six years, the team went from the German fifth division to the first division and finished second in its first season in the top flight. While RB Leipzig is Red Bull's most successful (at least on football's biggest stage) and best team, it wasn't the first club it bought.

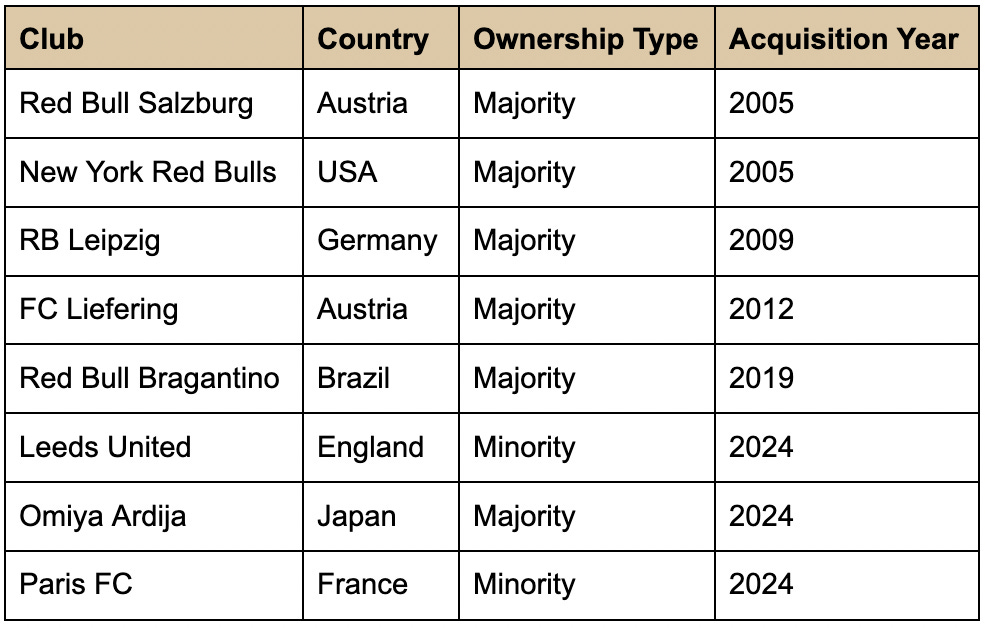

Red Bull acquired SV Austria Salzburg in 2005 and renamed the team Red Bull Salzburg. In fact, it has majority ownership in six football teams spanning Europe, North and South America, and Asia. Additionally, Red Bull has a minority stake in two other clubs.

In 2023, ESPN reported UEFA research showing that over 180 clubs worldwide were part of a multi-club structure, up from 40 in 2012. Red Bull isn't alone in its entrance into the world's most popular sport. The Saudis are very active in purchasing top clubs around the world. Even celebrities have gotten into the mix—look at Rob McElhenney and Ryan Reynolds' purchase of Wrexham in 2021 and their recent purchase of a minority stake in the Mexican side, Club Necaxa.

For Red Bull, it comes down to three key variables that have driven success on the field. Spoiler, it all happens before the games are played.

Tactics & Style: Red Bull recruits and trains its players to play a certain brand of football

Unified Global Scouting: Red Bull has arguably the best network of scouts around the globe, all working together for the Red Bull brand

Player Movement: Players in the system will work their way up to the best Red Bull teams as they improve

Tactics & Style

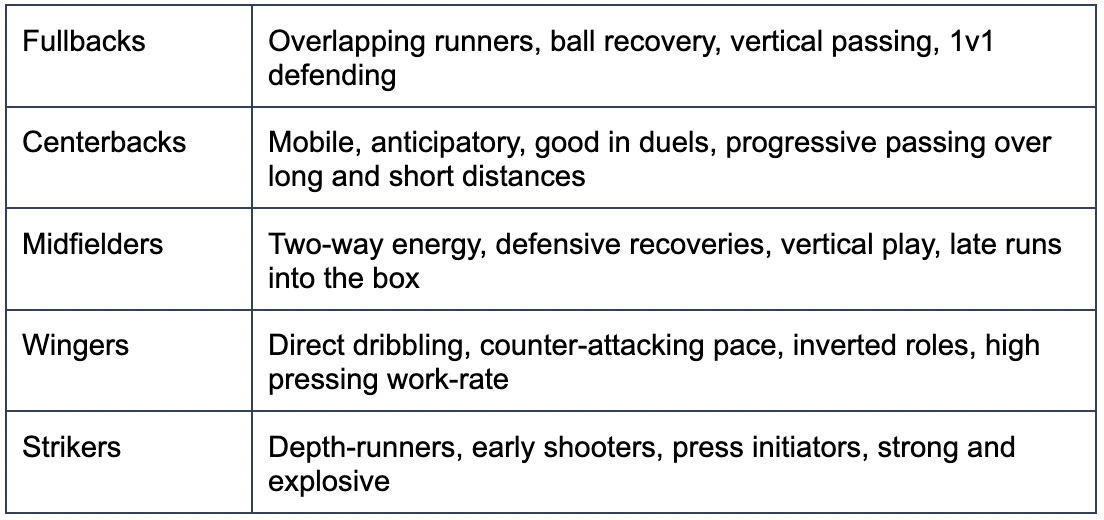

One thing Red Bull has done is create a distinct style of play. They play with energy and have adopted high-pressing football. Red Bull's clubs train and scout for this type of player.

Red Bull scouts look for players who have an instinct for when to pressure and when to sit back in compact zonal structures. Scouting for players who can play at a high pace with the ability to transition quickly helps to predict those who can meet the demands of top-flight football.

The Football Analyst has a great graphic that identifies key tactics and skills Red Bull looks for in players of different positions.

Unified Global Scouting

Red Bull scouts are relentless in their pursuit of talent, often identifying players 12-24 months before any other major clubs take notice. If a player looks promising based on the eye test and analytic measurements, they may be invited for a trial with one of their many teams around the world.

Red Bull isn't afraid to take calculated risks. It will sign players who may be raw or undeveloped, but show signs of elite talent, believing they can be molded once in the Red Bull system.

One of the reasons Red Bull has so much success is that all its clubs are interconnected. They act as one large club, sharing information about players and creating a large network of connected data from around the world.

Additionally, Red Bull intentionally scouts in places where there is less competition among other top clubs. Regions such as Eastern Europe, Scandinavia, South America, West Africa, and the USA/Canada are places where they have strong networks and ties to have their pick of the litter. With Red Bull clubs spread across continents, it also makes it easier to plug a player into its system without navigating too much legal red tape.

Player Movement

Red Bull is also disciplined in the way it operates the clubs. They focus on player development in the academy systems and refrain from big-money signings, unlike other governments and billionaires that have bought into the footballing world. Red Bull's business formula is simple. Grow and buy young players who fit the Red Bull mold. Develop them into stars. Sell them off to bigger clubs for a profit. All while trying to compete and be relevant at the highest levels.

Take Naby Keïta, for example. According to Transfermarkt, Red Bull only invested around €1.5 million in him, yet sold him to Liverpool for a fee of €60 million after just four years in the Red Bull System.

Before selling to bigger clubs, Red Bull players within the system are moved from club to club as they improve. Players will often start at FC Liefering, then graduate to play for Red Bull Salzburg, before finally going to Germany to play for RB Leipzig.

Red Bull treats its lower-tier clubs as a farm system similar to the minor leagues in baseball. These transitions are done smoothly because there isn't much negotiating necessary when it comes to transfer fees, etc. Sure, there are questions around fairness in the footballing world, but from a player's perspective, it is great that this system is in place to help them fulfil their dreams of playing in the best European leagues.

This type of player movement allows Red Bull clubs to compete without skipping a beat. Its clubs always have someone else ready to step up once a player is sold to a bigger club. When Keïta moved to Liverpool, Konrad Laimer and Amadou Haidara stepped up. When Dayot Upamecano was sold to Bayern Munich, Mohamed Simakan and Josko Gvardiol were ready to replace him.

While Red Bull's European clubs are firing on all cylinders, they acknowledge they haven't had as much success moving players from New York Red Bulls and Red Bull Bragantino to Europe.

Oliver Mintzlaff, the CEO of Corporate Projects and Investments at Red Bull, has shared his frustrations, saying, "MLS is developing, but it's developing far too slowly and is still far away from the standard we would imagine for a country like the USA."

In fact, only one player in the Red Bull system has made the continental jump, and that is US international, Tyler Adams. If Red Bull can get its North and South America pipeline of talent revving—look out. They will then have a truly worldwide tidal wave of talent working for their network of clubs.

The New Business of Football

Red Bull’s approach to football may feel unconventional to traditionalists. After all, this is a company that made its name selling energy drinks, not lifting trophies. But their global scouting network, unified playing style, and coordinated efforts across clubs show that they’re not just in the game to slap a logo on a jersey. They’re here to win.

At the same time, whether you're a kid on a dirt pitch in Ghana, a raw talent in Brazil, or a promising midfielder in Austria, Red Bull offers a clear path to the top.

That’s what makes Red Bull's model both exciting and controversial. On one hand, it fulfills dreams and proves that talent can be spotted and nurtured from almost anywhere on earth. On the other hand, it raises questions about the ethics of the game when corporations get involved. Either way, Red Bull’s multi-club empire represents the future of football.